While nature gives us ourselves—our bodies—it's the artist's job to describe our souls. When the painter Frank Auerbach (b. 1931) emigrated to England in 1939—he was born in Berlin in 1931—the idea or reality of Empire was uncertain, beginning to shift, and that change was most accurately reflected in the work of some of that era's more significant artists. The superb draughtsman, Vanessa Bell, began to wonder, in certain of her family-oriented canvases, if faith in family and love was sustaining enough in the modern world, while the brilliant novelist, Henry Green, in novels like Party Going (1939) wrote about how England's rigid class system was loosening its grip in an increasingly fractured and violent cosmos. But it was the English-born poet, W. H. Auden (1907-73) who spoke most ardently to the young; they read his sometimes gnomic texts as a way to articulate what their bodies, and their fragile souls, now felt in their once green and pleasant land, as anxiety, dread, and sadness crept in. The war sent those souls and millions of others spiraling. To kill one generation is to kill the next generation, and the next. Auerbach fled to England under the aegis of Kindertransport; his parents perished at Auschwitz. Auden settled in New York for some months when war broke out in his native land; he wanted to live and love more queerly as a man and an artist. When Hitler invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, the New York transplant commemorated this cataclysmic event in "September 1, 1939":

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:

waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odour of death

Offends the September night.

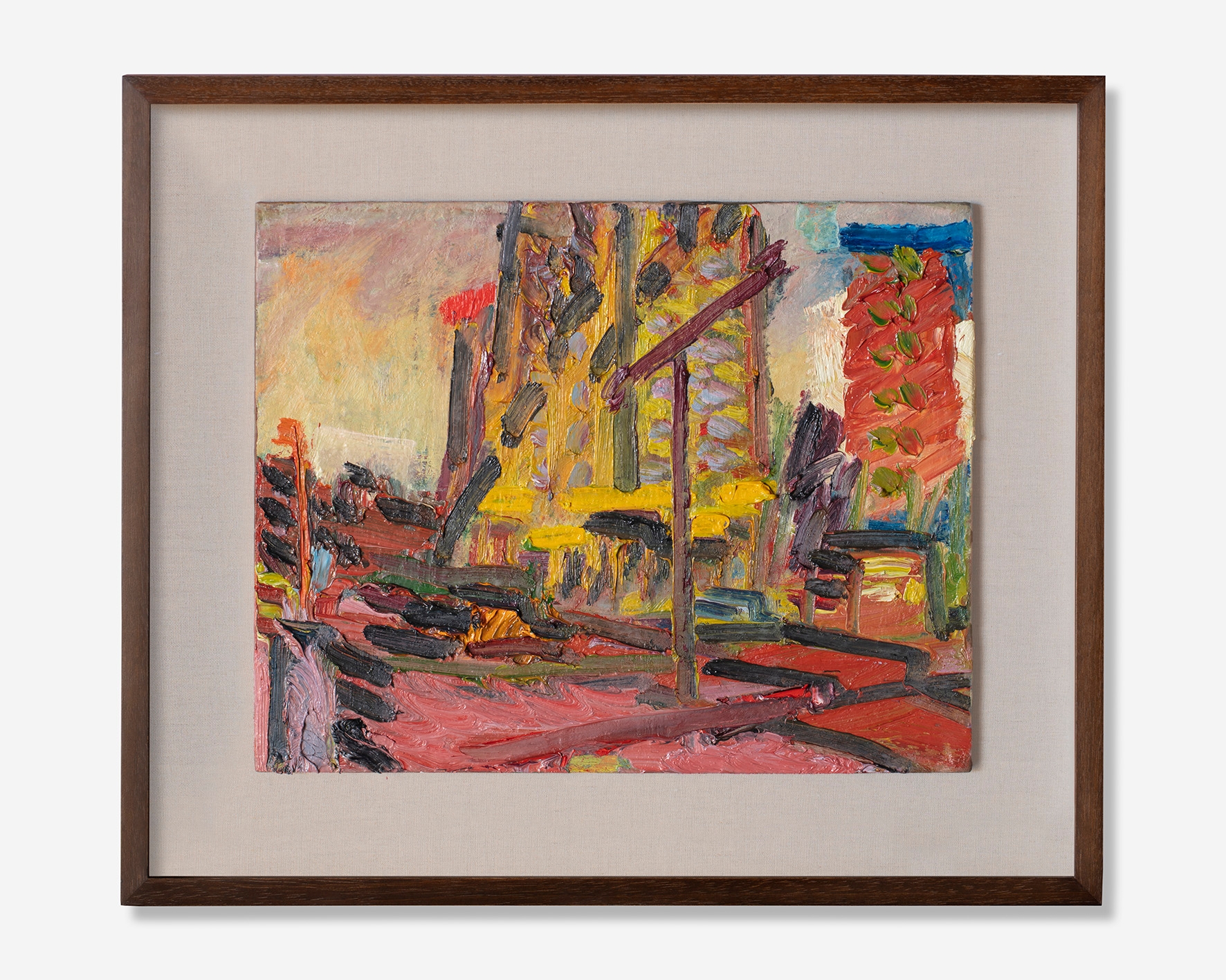

That dread—the fact of war's destruction, and how it casts on the world one long dark night—is certainly a dominant feeling in Auerbach and Auden's early work, when each artist articulated what it felt like not to have the ground solidly beneath one's feet, and to be far away from home, if ever one had one. In extraordinary early works, such as Auerbach's Building Site Near St. Paul's, Winter (1955), the artist stops the heart. Because in it one sees not only London remaking itself during the long, long years of post-War recovery, but the profound scars that lay beneath that recovery, the scars that are cut into the soul where there is no family on the other side of rescue. Marks on top of marks, a canvas where black dominates—looking at Building Site Near St. Paul's, Winter, we find ourselves in mourning for the world. And it's that sense of mourning that Auden evokes in "The Age of Anxiety" (1947).

A book length sort of urban eclogue, Auden's poem is largely spoken by the inhabitants of a bar who seek connection, intimacy, and purpose in an alienating, industrialized society. What chance did the soul have of surviving any of it? A world defined not by community but alienation. Was this world survivable? Have we survived it?

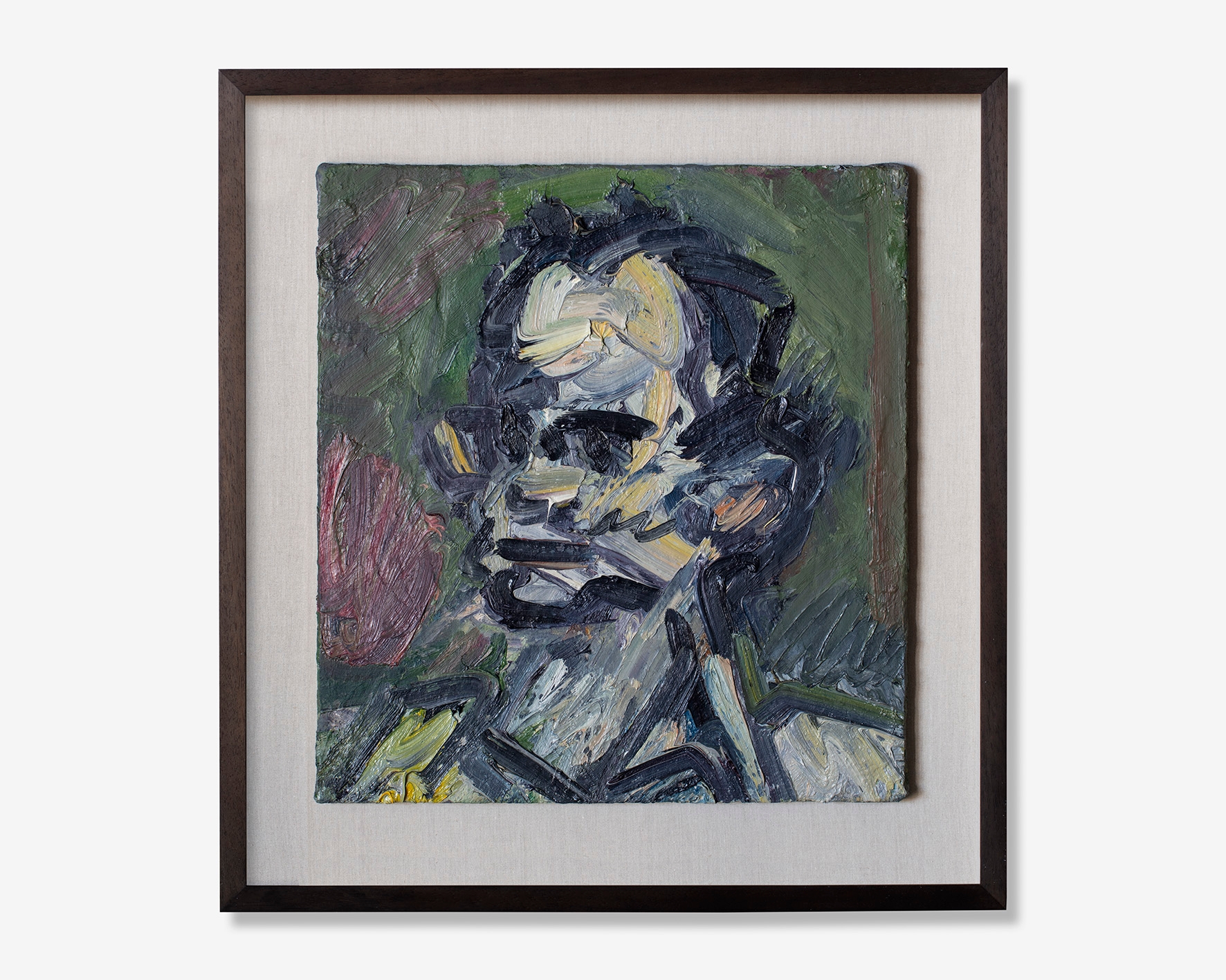

In Reclining Head of Julia III (1993), which is among the eleven unsurpassable pictures that curator Max Levai displays in his show, Frank Auerbach: Starting Again, now up at the historic Palazzo da Mosto in Venice, we see a head that's made heavy by paint—that is, Auerbach's famous impasto surfaces—but also being. The subject, Auerbach's wife, Julia Auerbach née Wolstenholme, is the painter's intimate; she has sat for him consistently since they met in their youth at the Royal College of Art in the nineteen-fifties. In this portrait, Mrs. Auerbach's head tilts back; what is she listening to? The years spent with the artist? Her family? Herself? It's not a silent picture.

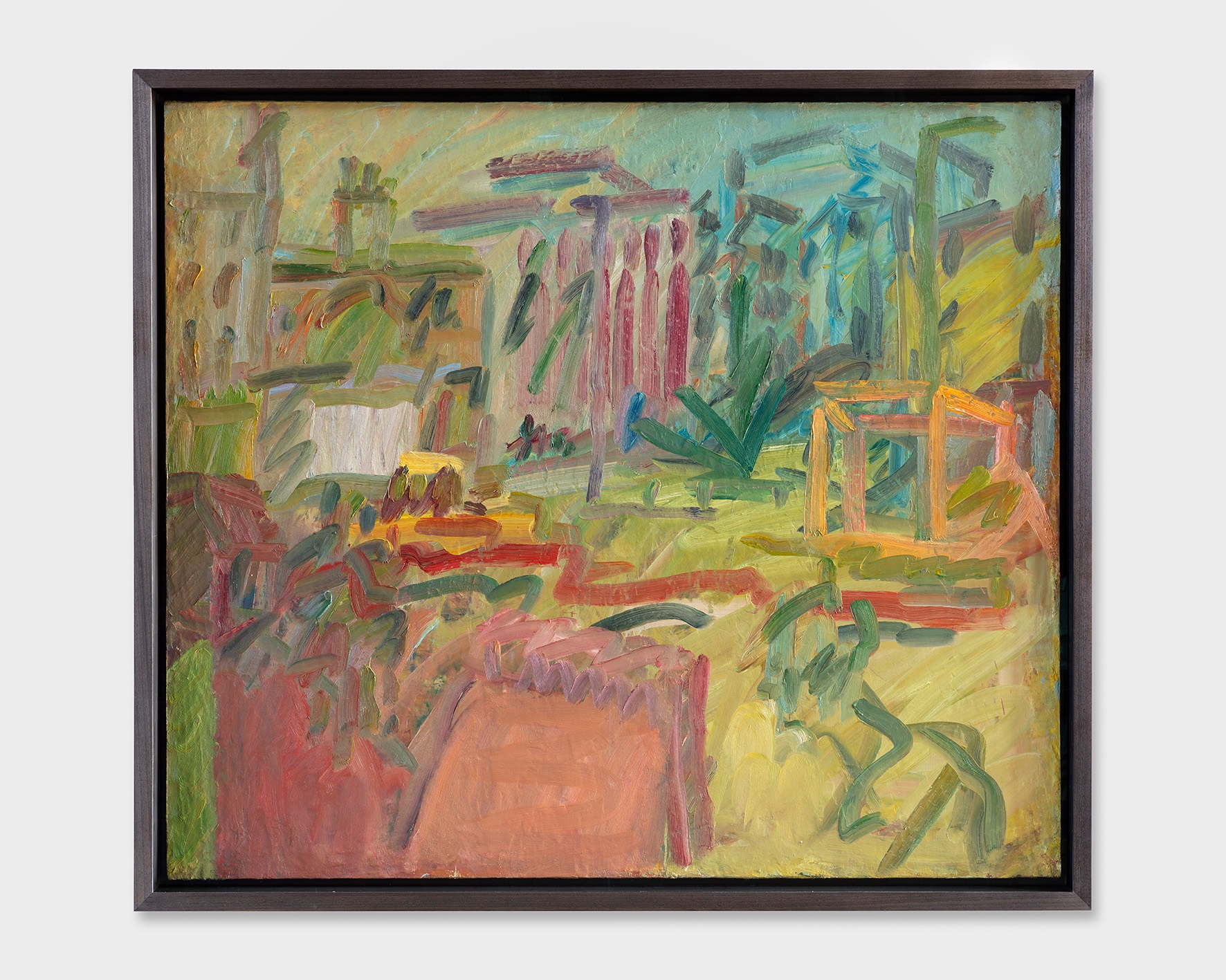

Auerbach's marks—made with various shades of black and a kind of salmon color for the head, and a brighter salmon color for the nose—are a cry about consciousness and time, and how each remakes the flesh, and the ways in which we paint the flesh. Despite being Auden's junior by some twenty-five years, Auerbach and Auden remain our exemplary poets of place—poets who believe in or, more accurately, trust in the magnificence of our survival at home, on that blasted out green, in the darker corners of the street, despite our will to destruction. Look at just one of the cityscapes included in Levai's show. Titled Christmas Tree at Mornington Crescent (2004-2005). The painting is large in scale, measuring 52 1/2 by 61 1/4 inches. Its size is in proportion to its depth. Auerbach, who has lived most of his adult life in Camden where Mornington Crescent—a terraced street—is located, doesn't use paint to depict architecture but, rather, how architecture can be used in the service of glorious paint. Oranges, yellows, greens, blues, are used not to display differences between trees and greenery and buildings, but the harmony that can be found in the scene's various differences. While Auerbach sees the painting as a whole, he's excited by the ways in which he sees the various parts as not whole (no building is "complete" with windows and stoop, for instance) and how best to move the work away from illustration to abstraction, which allows for more feeling, and less fixity. But certain questions arise while looking at this work, such as: Where are the people? What is the history of this place? We are in an urban space, but where are the people? Auerbach's spaces are dominated by silence, just as Auden's were dominated by words. Auerbach's Mornington goes on and on, but it's uninhabited—except by the artist who is looking at thing we then remake with our own eyes.

There's no denying that we live, now, in our own age of anxiety, and I wonder if this is exacerbated by our uncanny ability to survive our apparent need to express aggression and violence in order to feel more alive? The threat of death propels us to act. But as what? Picking flowers and striking our neighbor: the beauty of the everyday and the awful exists in all of us. In their work, Auden and Auerbach depict the sublime and the mundane, and how art is often framed by each. In his powerful and insightful poem, "Musée des Beaux Arts" (1939), Auden wrote:

About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer's horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

In Frank Auerbach: Starting Again, the "something amazing" we see in Auerbach's paintings is time made visible. And how when we draw on the "something amazing"—unnamed, inexplicable—that keeps us connected to art, artists, and the tremendous energy looking requires. And how it feeds the soul. "When one is young, one is excited by drama," Auerbach said once. "And when one is old, truth is exciting." The truth underpinning Auerbach's work—and Auden's—has a great deal to do with how each artist found their work: by understanding how appearances are meant to be deceiving, but why rest there? The real question being when you're looking, you're shuffling the deck in a metaphysical card game—and no one's the winner. The point is to keep going. I'm sure these lines of Auden's wouldn't be lost on Auerbach. From the poet's "If I Could Tell You" (1940):

Time will say nothing but I told you so,

Time only knows the price we have to pay;

If I could tell you I would let you know...

Perhaps the roses really want to grow,

The vision seriously intends to stay;

If I could tell you I would let you know.

Suppose all the lions get up and go,

And all the brooks and soldiers run away;

Will Time say nothing but I told you so?

If I could tell you I would let you know.

In addition to looking, Auden and Auerbach share a fixation on time. Where does it lead us? What is the narrative of that person's skin, the emotional weight of that building? In 1948, nearly twenty years before Auerbach won the Golden Lion while representing Great Britain during the Venice Biennale in 1986—Levai's exhibition is the first Auerbach exhibition to be installed in Venice since then—Auden began spending his summers in Italy. The culture, the sear and sea in his beloved Mezzogiorno freed him in many ways, and it was precisely that freedom that allowed him to go back—back to the boy whose obsession with language and form had its first home in the Pennines, when he was a boy. In masterworks such as 1948's "In Praise of Limestone," the poet was able to go back—back to the boy who saw not much of a separation between water and stone, and his own body:

If it form the one landscape that we, the inconstant ones,

Are consistently homesick for, this is chiefly

Because it dissolves in water. Mark these rounded slopes

With their surface fragrance of thyme and, beneath,

A secret system of caves and conduits; hear the springs

That spurt out everywhere with a chuckle,

Each filling a private pool for its fish and carving

Its own little ravine whose cliffs entertain

The butterfly and the lizard; examine this region

Of short distances and definite places:

What could be more like Mother or a fitter background

For her son, the flirtatious male who lounges

Against a rock in the sunlight, never doubting

That for all his faults he is loved; whose works are but

Extensions of his power to charm? From weathered outcrop

To hill-top temple, from appearing waters to

Conspicuous fountains, from a wild to a formal vineyard,

Are ingenious but short steps that a child's wish

To receive more attention than his brothers, whether

By pleasing or teasing, can easily take.

In Levai's installation, Auerbach's work lives now in a world of caves and conduits on an island that is sinking but remains upright, housing various religions, a multitude of history, and echoes upon echoes of stories and poems. There, in that place, the stones of Venice fold into its palazzos, its churches, its various mysteries that give us so much and take away, too, like waves on a beach always seem to do. In looking at Auerbach's various portraits assembled here in this watery world of stone, we draw close to the artist’s profound commitment to making a face, the layer upon layer of paint he requires to convey a soul. And in this gallery of bodies, heads, and hearts, one sees Auden's face, too, that famous rutted face with its fissures and layer upon layer of insight and care about the human spirit—a face Auerbach might have liked to paint, too, if only they had met.

Max Levai is pleased to announce Frank Auerbach: Starting Again, a comprehensive presentation of the acclaimed British-German artist in Venice, Italy. The exhibition will be on view from April 18 through June 28, 2024—coinciding with La Biennale di Venezia. Mounted at Palazzo da Mosto in Venice, the show marks a return to the city in which Auerbach won the Golden Lion at the Biennale in 1986. For the first time since that watershed presentation, work from nearly five decades of the artist’s creative production will be on display in the city. The exhibition will span two levels of the historic Palazzo da Mosto—built by architect Antonio da Ponte at the end of the 16th century, just around the corner from where he would go on to design the famed Rialto Bridge.

Uniting eleven seldom exhibited oil paintings made between 1969 and 2016, the exhibition focuses on Auerbach’s critical subjects: portraits of favored sitters and landscapes of the vistas he observes daily from his studio in London. By extension, the imagery which populates his paintings with near obsessive recursion is circumscribed to a handful of countenances of those same subjects he routinely depicts and the various sight lines just outside his studio in London. These are, however, relational worlds constructed through repeated returns—a reflection of the artist’s deep connection to his surroundings, those figures, faces, and forms he deems vital to his creative process. The exhibition unveils the expansive complexity of Auerbach’s seemingly hermetic practice, turning personal intimacy and feverish work in solitary environments into universally resonant ruminations on the human condition and the entanglement of visuality and interpersonal understanding.

To this point, Auerbach’s paintings are typically named after the depicted subject, attesting to his conception of the subject and their shifting images over the portrait process as the content of his work. These visages are encountered across the exhibition: Juliet Yardley Mills (JYM) was a contemporary he met at art school; a professional art model and close friend, JYM who sat for Auerbach twice weekly for over forty years. Another subject in the show, Paula Eyles appears in paintings from a protracted four year period, a dialogue which resulted in seismic pictorial advances for the artist. Throughout his career, Auerbach has also rendered those closest to him, including his son Jake—always portrayed in an upright position. Portraits of his beloved wife Julia, however, are invariably horizontally oriented. Sitting for Auerbach requires the understanding that paintings will be reworked, scraped down and re-layered until they are finished.

Each Auerbach painting extends a prismatic viewfinder onto a concentrated mode of making. Following from obduracy and experimentation, these attitudes wrap around his portraits (perhaps more accurately monumental, cocked heads than likenesses) and drive his architectonic landscapes (angular infrastructures that impart thick air, cloistered cities, and psycho-geographic vibration). As Auerbach confessed in a recent interview, his iterative practice is one which works, reworks, erases, and remakes—“I shall go on with that process for as long as it takes.” The agonism of painting is intonated by the finished compositions, where strident gesture lends a structural fragmentation that aligns with constant formal reconfiguration. Each line quivers with a tentative touch that conveys the ephemerality of feeling and perception, an apprehension towards totality and resolution.

The exhibition is accompanied by an essay on the artist by the Pulitzer Prize winning writer and critic Hilton Als. In this text, Als approaches Auerbach by way of the British-American poet W. H. Auden, whose own meditations on texture and landscape in and around London afford new insights into the lineages and resonances of Auerbach. Situating the painter within this poetic framework, Als enlivens the centrality of London, place, environment, and surface to the work of each. Illuminating the plausible dialogue between these two documentarians of British life, Als also attends to the crucial significance of staging an exhibition within a “vanishing city,” limning themes of impermanence and the provisional and contemplating the implications of these works in a space built of limestone, what Als calls “soft rock,” and surrounded by water. These shape-shifting dynamics come to the fore in relation to Auerbach’s fugitive imagery.

A supplementary essay on the history of Palazzo da Mosto by architect Francesco da Mosto will also be published on the occasion of the exhibition. Like Auerbach’s paintings, the Palazzo offers a metaphor of layered histories that start with the Mutis, a family of silk merchants from Bergamo who purchased a row of houses to make way for the palazzo as Venice became a trade center and crucial point of distribution with the East. After the Muti family were forced to sell the palazzo in 1669, the Acquisiti family undertook renovations, but ultimately sold the property soon after to Francesco Vezzi, who had obtained secrets to making porcelain from the Stolzen porcelain factory in Vienna. From this point forward the house changed hands several times during the 17th century until it was purchased by the Baglioni family, who specialized in the production of religious books and are responsible for the plasterwork, interior detailing, commissioned frescoes, and design that remain in the palazzo to this day.

— Megan Kincaid

Max Levai è lieto di annunciare Frank Auerbach: Starting Again, un'esposizione approfondita dell'acclamato artista britannico-tedesco a Venezia, in mostra a Palazzo da Mosto dal 18 aprile al 28 giugno 2024 in concomitanza con La Biennale d’Arte. L'esposizione rappresenta un importante ritorno a Venezia per Auerbach, che vinse il e il Leone d'Oro alla Biennale del 1986. Per la prima volta da allora, in questa storica presentazione, le opere di oltre cinque decenni di produzione creativa dell'artista saranno esposte in città. La mostra si estende su due livelli dello storico Palazzo da Mosto, costruito dall'architetto Antonio Ponte alla fine del XVI secolo, a pochi passi da dove avrebbe poi progettato il famoso Ponte di Rialto.

Unendo undici dipinti a olio raramente esposti realizzati tra il 1969 e il 2016, Starting Again si concentra sui temi tipici di Auerbach: ritratti dei suoi soggetti preferiti e i paesaggi che osserva quotidianamente dal suo studio a Londra. Gli immaginari relazionali di Auerbach sono costruiti attraverso la ripetizione, riflettendo la profonda connessione dell'artista con il suo ambiente, le figure, i volti e le forme che ritiene essenziali nel suo processo creativo.

Starting Again rivela l'ampia complessità della pratica apparentemente ermetica di Auerbach, trasformando l'intimità personale e il suo lavoro febbrile e solitario in riflessioni universalmente risonanti sulla condizione umana e sull'intreccio tra immagine e comprensione interpersonale. Ad oggi, i dipinti di Auerbach sono intitolati con il nome della persona raffigurata, attestando proprio la concezione del carattere mutevole del soggetto. Questi volti si incontrano lungo tutta la mostra: Juliet Yardley Mills (JYM) era una contemporanea incontrata alla scuola d'arte; modella professionista e grande amica dell’artista, JYM ha posato per Auerbach due volte alla settimana per oltre quarant'anni. Un altro soggetto nella mostra, Paula Eyles, appare in dipinti realizzati nell’arco di quattro anni, in un dialogo prolungato che ha portato ad avanzamenti pittorici di grande impatto nel percorso dell’artista. Nel corso della propria carriera, Auerbach ha anche ritratto i membri della sua famiglia, il figlio Jake, sempre raffigurato in posizione eretta, e la sua amata moglie Julia, ritratta invece quasi invariabilmente in posizione orizzontale.

Posare per Auerbach presume la comprensione che le sue opere verranno rielaborate, stratificando a spesso raschiando via la vernice, fino a quando non l'autore non le giudica complete. Ogni dipinto di Auerbach estende un mirino prismatico sulla concentrazione intrinseca nel suo modus operandi. Dalla sua caparbietà e sperimentazione nascono le peculiarità che guidano i suoi ritratti—forse più precisamente teste monumentali e arcuate che sembianze di persone—e i suoi paesaggi architettonici, infrastrutture angolari che imprimono aria densa, città recluse e vibrazioni psicogeografiche. In una recente intervista, Auerbach stesso rivela che la sua pratica iterativa è composta di lavoro, rielaborazione, cancellazione e rifacimento: "Continuerò con questo processo per tutto il tempo che esso richiede." L'agonismo della sua pittura si ritrova nelle opere finite, dove il gesto stridente conferisce una frammentazione strutturale che si allinea con una costante ri-configurazione compositiva. Ogni linea sembra tremare attraverso un tocco, un tentativo che trasmette la fugacità del sentimento e della percezione, l'apprensione verso la totalità e la risoluzione.

La mostra è accompagnata da un saggio sull'artista dello scrittore e critico vincitore del Premio Pulitzer Hilton Als. Nel testo, Als si avvicina ad Auerbach attraverso il poeta anglo-americano W. H. Auden, le cui meditazioni sulla texture e sul paesaggio di Londra ed i suoi dintorni offrono nuovi spunti sulle genealogie e le risonanze di Auerbach. Situando il pittore all'interno di questo quadro poetico, Als ravviva la centralità di Londra, di luogo, ambiente e superficie nel lavoro di entrambi. Oltre ad illuminare il plausibile dialogo tra questi due documentaristi della vita britannica, Als si sofferma anche sul significato cruciale dell'allestimento di una mostra in una "città che sta scomparendo", delineandone i temi di impermanenza e provvisorietà, contemplando le implicazioni di questi dipinti posizionati in uno spazio costruito di calcare, che Als chiama "roccia morbida,” e circondato dall'acqua. Queste dinamiche mutevoli trovano una corrispondenza nell’immaginario fugace di Auerbach.

Starting Again è completata da un saggio sulla storia di Palazzo da Mosto dell'architetto Francesco da Mosto, pubblicato in occasione della mostra. Similmente ai dipinti di Auerbach, il Palazzo è metafora della ‘stratificazione’ di storie stratificate ad esso associate, che iniziano con i Muti, una famiglia di mercanti di seta di Bergamo che acquistò una fila di case per fare spazio al Palazzo, al tempo in cui Venezia divenne un centro commerciale e un punto cruciale di distribuzione con l'Oriente. Dopo che la famiglia Muti fu costretta a vendere la casa nel 1669, la famiglia Acquisiti intraprese ristrutturazioni, ma fu presto costretta a vendere nuovamente la casa a Francesco Vezzi, che aveva ottenuto dalla fabbrica di porcellane Stolzen di Vienna i segreti per la produzione della porcellana di Meissen. Da questo momento in poi, il Palazzo cambiò proprietà cinque volte durante il XVII secolo, finché o non venne acquistato dalla famiglia Baglioni, specializzata nella produzione di libri religiosi, che arricchì la dimora degli stucchi, dei dettagli interni, degli affreschi e di buona parte dei mobili realizzati per il palazzo ancora oggi presenti in situ.

— Megan Kincaid

The 17th century Palazzo Muti, located amid the labyrinthine city of Venice, stands out not only because of its height, but also due to its sophisticated and inventive design. As Francesco Sansovino, son of the architect Jacopo Sansovino, wrote in his Most Noble City, Venice: “Among the most notable palaces in the world should be counted Palazzo Muti at San Cassiano, which is a stupendous and singular building, though it would appear more of a marvel had it been built along the Grand Canal.”

A group of small houses on the site, visible in the 16th century De’ Barberi map, were bought by the Muti family, silk merchants from Bergamo, with a view to constructing their great new house—themselves having come to Venice to take advantage of the new local skills in weaving silk and wool, which had developed there. To build their Palazzo, the Mutis chose Antonio da Ponte, a trusted Venetian state architect and outstanding engineer, who had designed the 316 meter long rope works (Corderie della Tana) in the Arsenale, and Venice's fortresses in Dalmatia, and who was shortly to complete the new Rialto bridge, built between 1588 and 1591.

Ever since the days of the Mutis, every family who owned the building established various activities inside it, thanks to the idea of the Palazzo as a “Fondaco”: a home and a business, all wrapped up into one. Indeed, the Palazzo was the family’s home and residence, a factory with storage spaces, commercial offices and showrooms, while also including a ballroom and official reception rooms, in line with the classic Venetian tripartite scheme.

Palazzo Muti’s exterior facades are an integration of medieval styles and the understated Classicism of Sebastiano Serlio, with one of the key elements in the Renaissance modernisation of Venice’s palazzi. Both exteriors have a similar design, but the landward facade bends like an amphitheater at the point where another diminutive street, the Calle di Ca' Muti, meets the main door. The curious wind-tunnel effect of the street below led it to be nicknamed “Calle del Vento.” The androne, or lower central hall, links the canal to the calle on one axis, and the two lateral courtyards on the other. Each courtyard had its own well to collect rainwater.

In Venice, the basis for all aspects of life was fresh water, which may indeed also become true in the future. Inside the Palazzo are two wells, one consisting of an ancient Roman column, which served as a well-head for a previous house on the site, and the other was built with the Palazzo in the Renaissance style. At the time, water would be used three times over. The first, when it was still clean and fresh, was for cooking, the second was for washing fabric or painting silk, and the last use for mixing cement mortar powder. In Venice it very quickly became clear that everything was done with a dash of “Art.” For example, the Verona marble well in the Renaissance style in the androne takes the form of an aedicule with columns, bronze fittings and wooden sculptures—possibly by the German Franz Pauc, who worked with Longhena in the library of San Giorgio Maggiore using similar motifs, theatrically positioned opposite the main staircase. Downstairs, modestly executed painted hall benches with high cut-out backs decorated with coats of arms stand against the androne walls.

The early Renaissance motif is seen also on the main staircase from the androne to the portego on the first floor, adorned with multi-coloured marbles in a geometrical pattern. The portego, in the shimmering but plain chestnut-brown floors made of the flexible Venetian marble-and-mortar compound, is lit by leaded glass windows made of small, irregular octagonal panes. The plasterwork on the walls owes to a later period, dating to the 18th century, as is much of the Palazzo's furniture.

As in most other cases in the history of these huge houses at the hub of Venice’s trading empire, the Mutis did not remain its proprietors for long. In 1669 they sold the house to the Acquisti family, documented by the 1686 engraving by Coronelli. But, only 30 years later, the Acquistis themselves had to sell the house to Francesco Vezzi, who had obtained from the Stolzen porcelain factory in Vienna the secrets of making Meissen porcelain, and by 1720 he was making satirical and burlesque figures in Venice on Oriental models. In 1737, a fire spread from a nearby house during a wedding party, causing 31,000 ducats worth of damage to Palazzo Muti, and after a period during which it was rented to various European royals, the Vezzi, in turn, had to sell, and it came into the possession of the Baglioni family. The Baglionis, from Lombardy, built up interests in printing, another of the city’s traditional businesses. Under a special license from the Patriarch of Venice, they specialized in the production of religious books and bookselling.

The decorations commissioned by the Baglionis were prompted by their children’s weddings. Various artists were employed for the decoration of different rooms, elaborately adorned with stucco-work, frescoes, and gilding. An allegory of good and evil in marriage, the groom with his hands chained and four overdoor figures representing two feminine virtues and two vices, are by Jacopo Guarana, who the year before worked on paintings in Ca' Rezzonico. In the small dining room, too, the ceiling is decorated with mythological scenes by Guarana, which continue the theme of marital dangers. Then there is an immense mirror filling the space on the rear wall between two windows, and another ceiling fresco, The Triumph of Art by Francesco Zugno, Tiepolo's most able pupil. This shows Apollo protecting the arts against the threats of time with figures of Diligence, Intellect, Drawing and Invention in each corner.

In the other wing of the house, the artist chosen was one of the most prestigious in Venice: Giambattista Crosato. Here, Juno presides over her heavenly domain in an allusion to the well-ordered domestic life of the Baglionis at their residence in the country at Massanzago, where the Venetian dramatist Carlo Goldoni, a family friend, was known to have worked. The theme is repeated in the frescoed walls of the large dining room, where the pleasures of their villa garden were depicted by David Rossi, and where flickering candlelight makes the architectural images three-dimensional.

The chapel, and the adjoining miniature boudoir, are located at the end of the south-west sequence of rooms on the first floor (piano nobile). The fact that it has its own roof suggests it was part of the original concept. Its position leaves a four-story lacuna at the end of the facade above street level: a channel to the Divine unobstructed by profanities with a putto on the chapel ceilings.

Palazzo Muti remained in the Baglioni family until 1919, when it was sold to the historian Andrea Da Mosto. The Da Mosto family has played a prominent part in the affairs of the Republic of Venice and its subsequent history for the last thousand years. They acquired an estate at Torre di Mosto, near Jesolo, but remained in the city at Ca' Da Mosto, a Byzantine house still standing in the parish of Santi Apostoli along the Grand Canal.

Political, judicial, and naval responsibilities in Venice were inseparable from mercantile duties, which perhaps explains the success of one of the Venetian Empire's heroes: Alvise Da Mosto (1433-88). In 1454, he obtained the support of the King of Portugal’s son, Prince Henry the Navigator, for a voyage down the west coast of Africa. Two years later, in 1456, he undertook a second voyage, during which he discovered the Cape Verde islands by chance. He wrote detailed accounts of the peoples of Gambia and Senegal, and of the gold trade, and these long remained in print in Venice. The story of this patrician Venetian family almost came to an end with Napoleon, since, of all the twenty children living at that time, only one line bore fruit. It was the present owner's grandfather, a high-ranking official in the Austro-Hungarian empire, who rediscovered his Venetian heritage, and returned to the city.

His son, Andrea Da Mosto (1868-1960), was director of the State Archive, and in 1940 he compiled its first catalog and index, consisting of more than 50 kilometers of documents, still used today, as well as published a history of the Doges of Venice. After buying Palazzo Muti, he introduced the Da Mosto history by filling the empty frames in the portego with copies of family pictures, including a map of Alvise Da Mosto's voyages, copied from the version by Grisellini in the Doge's Palace. In recent decades the house has fascinated filmmakers, including Luchino Visconti, who filmed Senso here, and Joseph Losey, who used it in Eva. It also appeared in The Talented Mr. Ripley by Anthony Mingella.

In addition to continuing to maintain an important historic building, the current owner, Ranieri Da Mosto, and his wife, Maria Grazia, have undertaken the refurnishing of its main spaces, using historic and family pictures and other contents appropriate to the various periods. The new scheme not only includes the piano nobile but also the attic, which has astonishing views over Venice's skyline. Indeed, the attic has been transformed in a manner akin to French artists’ studios. Notably, it was there that the painter Tancredi Parmeggiani announced the first sale of one of his paintings to Peggy Guggenheim. So the Venetian Palazzo as a Fondaco meant work, business, and art and, from the mid-15th century, art became the most important of these three elements.

On May 29, May, 1453, Sultan Mehmet II’s army of Turks marched into Constantinople, and took the city. Venice had lost her most important Imperial outpost. Now the Islamic Ottoman Empire dominated the East. This aggressor posed the greatest threat to Venice’s very existence. Venice did everything possible to make friends with the Turks. But rather than send a politician to Constantinople, they sent an artist: Gentile Bellini. As an ambassador and diplomatic representative of Venice, Bellini painted the portrait of Sultan Mehmet II. Venice was always a place synonymous with politics and money, but now Art was becoming as important to the city as its power and wealth.

As Gentile Bellini was on his diplomatic mission to Constantinople, his brother painted the Venetian leader Doge Leonardo Loredan, the man who had brokered the peace mission to the Ottomans.These two portraits tell a fascinating story: the Sultan was Muslim, and the Doge was a Christian. By rights, they should have been enemies, as the Pope himself wished, but business has always been more important than religion to the Venetians, and trade flourished. Here you can still see a mixture of science and art, and I think it is fantastic that Venice is still one of the world's major meeting points of Art, all these centuries later, connecting past and present.

Palazzo da Mosto/Muti Baglioni

Calle de Ca’Muti o Ca’ Baglioni

S. Polo 1866 30125